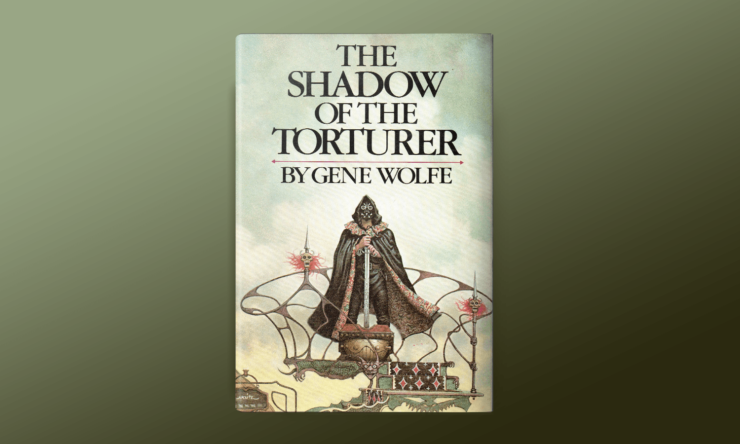

I first encountered Gene Wolfe’s work when I was a sophomore in high school, when I accidentally stumbled onto the paperback of The Shadow of the Torturer at my public library. I picked it up not knowing anything about it, intrigued as much as anything by the fact that even though it was called science fiction it had a cover that looked like a fantasy novel: a masked and caped figure holding a massive sword. But it also had a blurb from Ursula K. Le Guin, whose Earthsea books I had loved, describing it as “the best science fiction I’ve read in years.” So, was this science fiction or fantasy?

This wasn’t clarified for me by the other words on the cover, where the book was described as a “world where science and magic are one” and, by Thomas M. Disch (a writer I wouldn’t read until years later) as “science fantasy,” a term I’d never heard before. Wasn’t science the opposite of fantasy? In short, I was confused and intrigued. I went into the book not quite knowing what to expect but feeling not unpleasantly off balance—which, I’m still convinced, is the best way to first encounter Wolfe.

Up to that point, I’d been reading fantasy and science fiction largely for escape. The quality of the imagination mattered to me, as did the originality of the concept, the quality of the writing less so—though I was beginning to be aware that the well-written books were the ones that stuck with me longest.

Every week I’d go to the SF/Fantasy paperback section in the library and browse around until I had a half dozen books to take home. If I liked a book, I’d read more by the same writer; if not, I’d choose another writer on the next visit. Being a somewhat anal kid, I usually started in the A’s and browsed forward until I had my books. The only reason I found Wolfe was because I’d come to realize that my usual method rarely took me past the M’s, and I started wondering what was going on with the writers found later in the alphabet. So, for once, I started at Z and worked backward.

Buy the Book

The Complete Book of the New Sun

I took The Shadow of the Torturer home and opened it. The first sentence—“It is possible I already had some presentiment of my future.”—struck me as mysterious and promising. There was something ominous on the horizon for this narrator. The narrative immediately jumped from there to a vivid description of a gate, a description that, by the end of the sentence that introduced it, had become a symbol for something about the narrator’s future self. By the end of that first paragraph, the narrator—Severian, an apprentice in the torturer’s guild—tells us that he’s begun the story in the aftermath of a swim in which he nearly drowned, though we won’t have the details of that swim for a little while. In just that first paragraph, then, we move backward and forward in time, have the doubly-focused sense of what things appear initially and how they come to function later in memory, and establish the narrator as someone who is actively rearranging the story he is telling.

The rest of the book lived up to, and further complicated, the complex texture of that first paragraph, following the apprentice torturer’s misadventures as he makes the decision to betray the principles of his guild, narrowly escapes execution, and is sentenced to exile as a carnifex (an executioner) in the distant town of Thrax. On the way he shares a room with a giant man named Baldanders and meets and joins fates with Dr. Talos, the manager of a band of itinerant players to which Baldanders belongs. There was also combat to the death by flower (kind of), a wandering through a strange Botanical Garden that seemed to weave in and out of time, a character who seems to arise without explanation from a lake in which the dead are laid to rest, and much more. It’s dizzying and exciting, and also full of moments that show their full significance only later, when we have more pieces of the puzzle.

The Shadow of the Torturer wasn’t, generally speaking, what I was used to with science fiction and fantasy (though later, as I read within the genre in a less haphazard way, I found other writers with a similarly rich complexity). It demanded more of me as a reader, demanded that I juggle several different plot strands and moments in time at once, but also rewarded me. I found the book dense and intense and mysterious; I loved the way that the less than reliable narrator led me through it, sometimes hiding things from me for quite some time. It was a challenge to read, the language itself Latinate and rich, and the narrative itself slyly shifting in its telling, so that I found I had to focus to keep everything straight. I encountered words like “fuligin” and “cacogen”, which I didn’t know and which I found I couldn’t look up, but had to figure out by context. The novel did, in that first read, feel more like fantasy than science fiction to me, though not quite like any fantasy realm I had experienced before. Still, there were subtle hints in this novel, and more in the novels that followed, that behind the seemingly medieval moments were hints of vaster realms and other worlds.

By the time I reached the end, I had as many questions as when I’d started, but they were different questions. The world itself was fuller, its outlines more precise. The novel ends with Severian passing through another gate, listening to a tale being told by a stranger, and that tale being interrupted by an eruption of violence. But before we can discover what happened, the book ends: “Here I pause. If you wish to walk no farther with me, reader, I cannot blame you. It is no easy road.” What a curious place to end a book, I thought, even if it is a book in a series.

I did indeed wish to walk farther. The next week I returned to the library, returned to the SF/fantasy paperback stacks, and returned the W’s, only to find that Shadow of the Torturer was the only Wolfe paperback my library had. But, when I asked, the librarian told me a new Wolfe had just come in, the hardback of the just-released The Claw of the Conciliator (now you know how old I am), the sequel to The Shadow of the Torturer. As soon as she put a card into the back of it and wrapped the jacket, I was welcome to it.

The cover of this hardback seemed even more like fantasy: the masked figure was still there, now shirtless, holding a glowing orb, surrounded by bone-wielding man apes. I opened it, eager to find out what had happened at the gate, and realized after a few paragraphs…that I wasn’t going to get that, at least not immediately. The narrative had jumped forward: what the narrator claimed to be a pause at the end of the last book was instead a skipping ahead. For a moment I thought I’d missed a book in the series. But no, this was the second book—the third wasn’t out yet. But by the time I realized that I wasn’t going to get the answer to what happened at the end of The Shadow of the Torturer, I was already intrigued by what was happening instead.

Those movements backward and forward in time, these caesuras, that manipulation by a narrator who, we gradually realize, is telling his story from a very peculiar position, is something that continues throughout The Book of the New Sun. Since that first reading I’ve gone on to read the whole series a half dozen times, and keep finding new things in the books each time. The Book of the New Sun is the kind of series that on the one hand can be endlessly studied (as the many online Wolfe forums testify) but also a book that is propulsive and satisfying in its own terms. In that sense it’s like Tamsyn Muir’s Locked Tomb trilogy, with its very different but equally heady mix of fantasy and sf: complex and satisfying and smart, full of puzzles, but with enough propulsive energy to keep you going even if you’re a little off-balance as you read. Wolfe, at his best (as he is here in Shadow & Claw) can be enjoyed for his puzzles and word games and complexities. But above all he can and should be simply read and enjoyed, for the subtlety of his narrators, for the deftness of his language, and for his embodied understanding that the way a story is told is far more important than the story itself.

Buy the Book

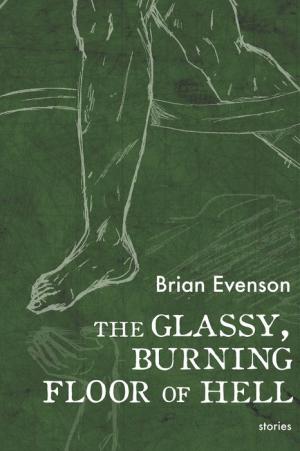

The Glassy Burning Floor of Hell

Brian Evenson is the author of over a dozen works of fiction. He has received three O. Henry Prizes for his fiction. His most recent book, Song for the Unraveling of the World, won a Shirley Jackson Award and was a finalist for both the Los Angeles Times Ray Bradbury Prize for Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Speculative Fiction and the Balcones Fiction Prize. He lives in Los Angeles and teaches at CalArts.